Research

For those who lived and wrote the story of data science at the University of Virginia, it is about much more than just the history of a school. For many of them, the creation of a school was far from their minds when this story began.

What would transpire over the years — and ultimately result in the creation of UVA’s 12th school and the first of its kind in the nation — was the product of fortunate timing, extensive outreach and planning, committed champions, and more than a little luck.

In the narrative that follows, we’ll trace the history of these efforts and the impact they would have. Later, the early days of the Data Science Institute will be chronicled, including the development of the master’s program.

Finally, you’ll learn about the creation of the School of Data Science, its mission, and the people who brought it to life and embody its purpose, culminating in the opening of the School’s new home in 2024 at the entrance to the Emmet-Ivy corridor in Charlottesville.

The story begins near the turn of the century, then picks up rapid momentum in the early 2010s as the eyes of the media and Washington begin to focus on big data and efforts that were already underway at UVA gain strength.

What would ultimately emerge would be a School Without Walls, dedicated to interdisciplinary research, collaboration, and the practice of responsible data science for the common good. Run by a handful of staff in the early days of the Data Science Institute, the School of Data Science would become what it is today through the commitment, dedication, ambition, and joy brought to the work by more than 100 faculty and staff, as well as an ever-increasing group of students and alumni.

For them, the story of data science at UVA is still being written, and it is one that began with just the seeds of an idea.

When Rick Horwitz came to UVA in 1999, he was looking for a new start to his research career. He’d most recently been at the University of Illinois, where he established the Department of Cell Biology, but he was ready to move out of administration.

“It was time to come to a place where I was unknown,” he said, adding that he was ready to set “a new direction” for his research. It would not take long for him to get that opportunity.

Shortly after Horwitz arrived at UVA, the National Institutes of Health launched a major new effort aimed at promoting large-scale, collaborative science. UVA would receive what was known as a “glue grant,” with Horwitz the principal investigator. The grant would fund an international cell migration consortium to better understand the invasion of cells.

The program spanned 10 years, and the research it produced required extensive collaboration across multiple disciplines. It also involved looking at data from a wide variety of sources, which got Horwitz thinking as the work of the consortium wound down: “Could I do something similar to catalyze collaborative research at UVA?"

In 2011, Horwitz moved into a new position — Associate Vice President for Research and Bioscience Programs — with a mission from his new boss, Tom Skalak, the University’s Vice President for Research, that was not without ambition. Skalak challenged Horwitz to “seed creative ideas and stimulate/motivate people to great achievements that were not visible before.”

Thinking back to his experience with the NIH glue grant, Horwitz was drawn to the idea of collaborations across Grounds but in work that went beyond just the biosciences. After pitching his broad, still-developing idea to Skalak, and receiving his blessing to move forward, Horwitz went to work.

“I went out, and I interviewed research deans and faculty,” he said, describing his next steps. “I just found anyone who’s doing quantitative stuff or had data or doing neuroscience,” he said, asking them about their work, their aspirations, and their data.

“Do you have data sets you’re not analyzing,” he recalled asking colleagues. “And if so, why aren’t you doing it? What are the bottlenecks, and what are the opportunities?”

He estimates that he interviewed 50 people. A theme was emerging — data, modeling — but, Horwitz said, Skalak, while supportive, was skeptical that Horwitz’s listening tour was yielding something concrete and actionable.

“There was no beef,” Horwitz said of his efforts at this time. “There wasn’t even a bun yet.”

Teresa Sullivan was no stranger to big data by the early 2010s. She worked with Census data — perhaps the crown jewel of big data sets — while completing her doctoral dissertation in the early 1970s at the University of Chicago.

“It was very time consuming, clunky compared to what you do today,” she recalled of the tapes she pored over in order to extract what she needed. It was tedious work, but she developed a knack for it, even catching an error that the Census Bureau wound up correcting. Decades later she would write a short book about the controversies surrounding the 2020 Census.

The 1970 Census may have been Sullivan’s first experience with big data, but it would hardly be her last.

In 1985, Sullivan, then a sociology professor at the University of Texas, was having lunch with two law professors, who were bemoaning the fact that it was difficult to assess whether recently enacted bankruptcy reforms were effective. Sullivan had an idea — look at the data.

She took the two professors — one of whom was future U.S. Sen. Elizabeth Warren — to the federal courthouse in San Antonio where they pulled a random sample of 150 bankruptcy cases and then coded them, a process, Sullivan recalled, that was much more cumbersome in the mid-1980s than it would be today.

Their hard work, though, yielded some compelling results, and they would eventually receive funding from the National Science Foundation and expand their study to other states. Their findings that bankruptcy laws were often not working as intended met some resistance. But the data ultimately won out.

“A lot of people said we were just wrong,” Sullivan recalled. “And there ensued a lot of controversy and some follow-up research. And our work passed from completely wrong to conventional wisdom in about five years.”

Sullivan would hold a variety of senior administrative roles at the University of Texas and the University of Texas System until 2006, when she was named provost and vice president for academic affairs at the University of Michigan.

After four years in Ann Arbor, Sullivan, in 2010, was tapped to become the University of Virginia’s eighth president. She would be the first female to hold the office and would serve for eight years. Her ascension to the top leadership post at UVA would prove fortuitous for data science at UVA.

On Sept. 18, 2019, the School of Data Science became the University of Virginia’s 12th school and the first school of data science in the nation, a moment years in the making that positioned UVA as a national leader in this rapidly growing field.

Guided by the aim of creating a collaborative culture and founded on the promise of interdisciplinary research, it would become the School Without Walls that Phil Bourne and others had envisioned.

Bourne, director of the Data Science Institute, would become the first Stephenson Dean of the School of Data Science, which was made possible by an endowment funded by commitments from Jaffray Woodriff and the Quantitative Foundation, UVA’s Bicentennial Professors Fund, and a newly announced $3 million gift from Scott and Beth Stephenson, which matched an earlier donation of that amount that they made in 2014.

The Stephensons had been longtime supporters of the University, including the Data Science Institute. In a 2019 news announcement about the gift, Scott Stephenson, who continues to serve as chairman of the School of Data Science advisory board, said, “The expanded scale of the School will help fulfill the vision of data science as a domain of knowledge reaching across all parts of the University.”

So, what was one of the top agenda items for a new school dedicated to data science?

“One of the first things we did was really to step back, a bit ironically in a way, and say to ourselves, what is data science?” said Bourne, noting that 10 different people might offer up 10 different definitions.

“We felt it would be really important if we all started off, to some degree, on the same page,” Bourne added.

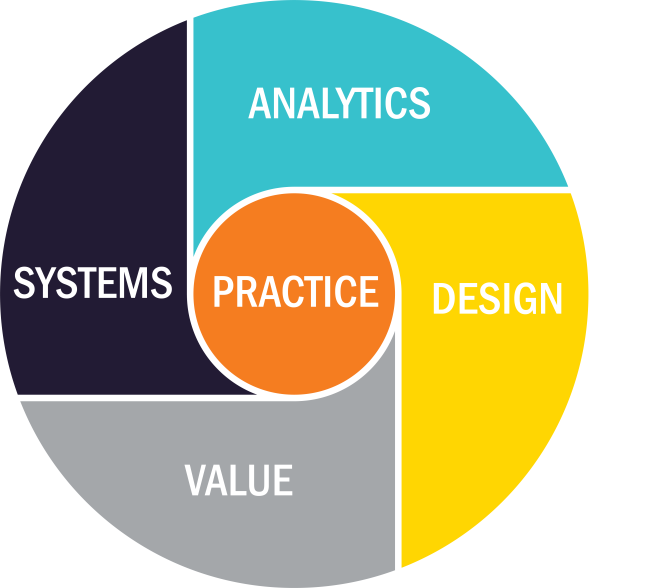

Out of these discussions came the 4 + 1 Model, an effort to better define data science that was heavily influenced by Rafael Alvarado, an associate professor.

The model lays out four areas of data science — Value, Design, Systems, and Analytics — connected by a fifth area, Practice, which are the activities that occur when expertise from each of the four areas are brought together.

Using that model, the School offered up this definition of data science:

“Data science is a convergent field that integrates expertise from four broad areas of knowledge — value, design, systems, and analytics — with the purpose of extracting information, insight, and value from data in a responsible, authentic, and actionable manner. Data science concerns more than data analysis — it includes the broad and directly relevant contexts in which data analytic work takes place.”

The 4 + 1 Model continues to serve as a cornerstone of the School of Data Science both in education and research.