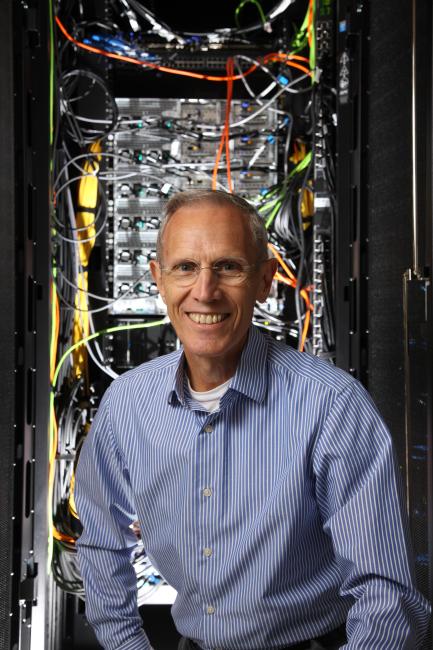

The Data Science Institute began its work in September 2013, with Don Brown as its founding director.

Jeff Holt, a professor of statistics and mathematics, also joined the institute as its program director, charged with advising, managing, and overseeing academic matters pertaining to the soon-to-be created master’s program in data science.

“I pushed strongly for the institute to have a teaching component,” Brown said, recalling early discussions about the mission of the Data Science Institute. “I felt it was absolutely critical for us to become a leader in teaching what we were then starting to call data science.”

Developing the curriculum was a collaborative process, with Brown working with colleagues across the University.

“We had faculty members from engineering, from systems engineering, from computer science, and from statistics that were all involved in creating that curriculum,” Brown said.

While launching a master’s program by the end of the academic year was a critical priority for Brown, it was hardly the only one. One was recruiting faculty — not to the Data Science Institute directly but to other UVA schools, such as the Schools of Engineering and Applied Science and Medicine, where they would serve as collaborators with the institute.

Another issue Brown was involved in early on was in research computing, an area where UVA’s infrastructure was lagging.

“So, we took over,” Brown said, noting that institute funding and efforts helped bring in major research computing systems, including a $2.4 million high-performance computing cluster, known as “Rivanna,” which was officially launched at UVA on Sept. 18, 2014.

Based just on her undergraduate transcript, Arlyn Burgess may not seem the obvious first staff member hired by the Data Science Institute in early 2014. An oboe performance and religious studies major, Burgess was a 2009 graduate of Northwestern University.

She came to Charlottesville shortly thereafter to join her now husband who was in a doctoral program at UVA. She inquired with a local oboe teacher about jobs and discovered one at the University’s Department of Music in administration. It would prove to be eye-opening.

“Very quickly I realized that, since I was just out of college, there was a whole side of higher ed that I never understood as a student,” she said.

Burgess would eventually move from a student-facing role to one where she oversaw the graduate program and learned about the finances involved. Her interest in the field led her to obtain a master’s degree in education, focusing on higher education, particularly the quantitative aspects of administration and planning.

Meanwhile, by 2014 it had become increasingly clear to Don Brown that the nascent Data Science Institute needed help.

“I was realizing that we were really starting to hemorrhage in terms of the amount of things we were trying to do,” he said. “It was just getting incredible.”

While Burgess did not have a background in data science, she conveyed her passion for the field during her interview, a quality that proved to be exactly what Brown was looking for.

“Wow, this is what we need,” he remembered thinking after meeting with Burgess. “We need people who are enthusiastic about this because this can be a lot of work.”

Burgess would become the first staff member hired by the Data Science Institute. She vividly recalled her first day.

“I met Don there, and he opened up the door, and he said, ‘Here’s your office,’” Burgess recalled. “And it was a completely empty room, tiled floor — there were lights, but there was no furniture.”

So, Brown gave her a very sensible first assignment: buy some furniture. “I knew from that point on that it was going to be a build it as we go,” Burgess said of the institute, which, for years, would operate out of spartan office spaces, including a red shed at the Dell 1 building on Grounds.

After getting settled in, Burgess would soon embark on an outreach mission, building relationships across the University that could help propel the new institute forward.

“I spent very little time in my office,” Burgess said. Instead, she worked in places like the dean’s office at the Engineering School or the library, while, at the same time, getting to know key people in the Departments of Computer Science and Statistics.

“I basically built a team of people who were interested in working on data science,” she said. Above all, her job was “data science evangelist,” connecting the people and points of interest of data science to move the institute forward.

Her efforts, along with those of Brown and Jeff Holt, would reap benefits that summer as the Data Science Institute admitted its first cohort of master’s students.

The Data Science Institute was breaking new ground in many ways, one of which was that, in addition to its research mission, it would also have the ability to confer degrees — a first for an institute at UVA.

“None of the other institutes that UVA formulated, these cross-school institutes, had a teaching component,” said Don Brown.

President Teresa Sullivan, who was keeping close tabs on the labor market and talking with employers, was also strongly supportive of the idea that the institute should produce data science graduates.

Employers “want to know that you’ve got expertise in data science — they don’t want to sit there and parse through your transcript and try and figure out if you do,” she said. By conferring data science degrees, they wouldn’t have to.

Brown’s objective was to establish a residential master’s degree in data science within the first year. It was an ambitious goal with plenty of challenges.

For starters, there was resistance from the UVA Faculty Senate, particularly from the Statistics Department.

“They were not happy about it, a data science program living outside of statistics,” Brown said. However, they didn’t have nearly enough voting power to quash the idea. So, the master’s proposal went to the State Council of Higher Education for Virginia for final approval, which granted it enthusiastically.

The next mission was bringing in students, a tricky task that first year given that the program hadn’t yet been approved, which meant the institute couldn’t recruit applicants.

“I used to joke that they clearly were data scientists, because in order to discover our program, they had to be,” said Brown of that first class.

One way or another, word spread about the new program, and the applications followed. Ultimately, 175 people applied to join the inaugural 2014-15 master’s in data science cohort and nearly 50 would matriculate, a far higher number than Brown expected.

“They were extraordinarily excited because, of course, they were reading like everyone else that data science was really the field of the future,” he said.

That excitement proved helpful to Brown and his small staff as they worked to build a program from scratch.

“They just loved everything we did even when we didn’t know what we were doing,” Brown joked.

“It was unbelievable to see the different backgrounds that they came from and their enthusiasm to be the guinea pigs,” Arlyn Burgess said.

Despite growing pains and resource challenges, the first class would graduate on time in 2015. When they did, Provost John Simon leaned over to Brown and, underscoring the historic nature of a UVA institute conferring degrees for the first time, said, “Did you feel the earth shift?”

President Sullivan read the degree conferral with text she wrote herself: “I confer upon you the degree of master of science, with all the rights and privileges thereunto belonging and charge you to use your knowledge and skills to continue exploring, analyzing, and safeguarding data to make discoveries to advance the world, while treating data ethically and with regard to the privacy rights of individuals.”

By the program’s second year, the number of applicants to the data science master’s program had nearly doubled to 340.

Don Brown and others continued working to fine-tune the master’s program to make it more effective for students. “We created, basically, a foundation for what would become the curriculum in both the undergraduate and Ph.D. programs through what we were doing in the master’s program,” Brown said.

Part of the reason the curriculum needed to be continually reexamined and refined over the years was to ensure that it kept up with changes in data science.

“The field just continues to evolve with new breakthroughs in various ways,” said Brown. “And that’s what makes it so exciting.”

Meanwhile, plans began for an event to showcase the data science work that was now well underway at UVA.

“We knew that there were a lot of people doing data work,” said Arlyn Burgess. “We knew that there were a lot of people interested in working with other people that were doing data work. And honestly, we wanted people to see us as an ally.”

Burgess spoke with a friend in the office of the vice president for research, and an idea began to formulate around bringing people together from the UVA community who were doing data-driven research to let them talk about their work.

Burgess and the team reached out to associate deans for research at UVA schools, asking for candidates to discuss data-focused work. While the first Datapalooza, held on Sept. 18, 2015, was organized and funded by the Data Science Institute, it was truly a University-wide event, with representatives from all 11 UVA schools participating.

The institute “was the platform to showcase the data-driven research that was happening all over Grounds,” said Burgess.

Datapalooza would include panel discussions and a resource fair, as well as keynote remarks from Johan Bos-Beijer of the General Services Administration and Linda Abraham, the co-founder of comScore who would go on to serve on the board of the School of Data Science.

The event has “evolved over the years,” said Burgess.

“But that very first one was, how do we bring these people together?” she added. “How do we create a platform to elevate that conversation and get those people in conversation with one another?”

Datapalooza has been held every year since, and the conference continues to foster collaboration across UVA and promote data science. The name has also stuck, which Brown credited to Burgess.

“We still have Datapalooza, and that name still sounds right,” he said.

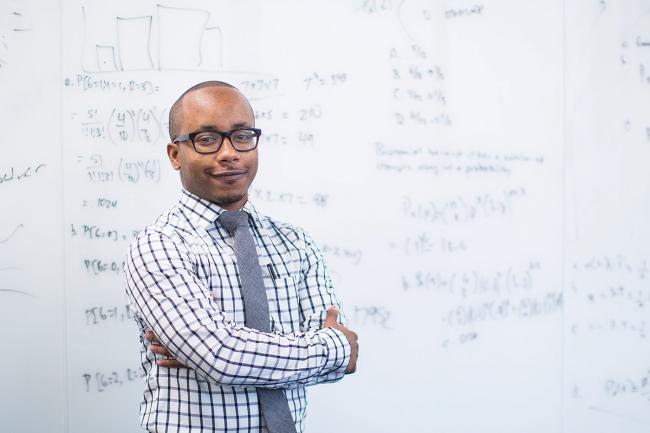

Job openings in data science continued to grow, but the professional landscape wasn’t always as well defined. When Reggie Leonard joined the Data Science Institute in 2015, it was more like the “wild West,” he said.

Job listings were at times confusing, and, in many cases, companies that weren’t actually doing data science were seeking data science applicants.

“It was really hard to help students figure out what jobs to apply to,” Leonard recalled.

Leonard knew something about professional uncertainty. He was a psychology major in college and remembers hearing from people who assumed he must be planning to go to graduate school since, they told him, there weren’t any jobs in his field.

“I realized how little reflection, and little space for reflection, I even had for making that decision for what was next,” Leonard said.

He would go on to graduate school, receiving a professional counseling degree at Liberty University, and found a new direction and purpose: career development.

After staying on at Liberty as a career counselor, Leonard learned about an opportunity that spoke to another interest of his: technology and innovation.

“Data science was on my radar, not necessarily as data science but more so as big data,” he said. He would join the Data Science Institute as assistant director of career services in June 2015, just after the first cohort of data science master’s students received their degree the month before.

Using LinkedIn, he reached out to as many new alumni as he could to make connections. “Have you landed something?” he said he would ask. “Let me see your résumé. Do you know how to interview for a data science opportunity?”

During that initial period, Leonard maintained his focus on building contacts with alumni and determined how he could best support them as they sought to launch their careers.

As time went on, Leonard’s career advice, like the degree program itself, would evolve to reflect the changing nature of the field.

“Two to three years into my time at Data Science, all business analysts and data analyst roles started to have R and Python” skill requirements, he said, referring to the programming languages. “The level of technical rigor for data scientists was increasing,” Leonard added.

In addition to Leonard’s work to build a career services component within the institute, an emphasis was also placed on ensuring master’s students were gaining the practical experience they would need through capstone projects.

In these projects, which continue to be required for graduation, students generally work with an academic, commercial, nonprofit, or governmental organization to develop a data science project designed to address a sponsor’s actual need. It’s a way for students to learn from, and hopefully overcome, the challenges that arise from tackling real, and often very difficult, data science questions.

“It’s a learning experience of how real data science works,” said Don Brown.

Arlyn Burgess recalled hearing from students who had been scheduled to present their capstone work to the institute’s advisory board during one of their initial meetings in 2015. The students were concerned they wouldn’t have anything compelling to show to board members because of the problems they had encountered.

“That sounds to me like your presentation,” Burgess said she told the group. It was an illustration of what Brown and Burgess referred to jokingly as the 80-20 rule: 80% of the time data scientists are cleaning and wrangling their data while the other 20% of the time they’re complaining about it.

Brown thought the experience was constructive for the board.

“I think the board members, when they met with students, that really helped them to understand that this was the way it was in the world and to expect that kind of thing,” he said.

Teaching students how to effectively present their research has long been an emphasis of Brown’s.

“We just constantly hammer talk about motivation,” Brown said.

“Why are you doing this? Why is this important to somebody?” he says he tells students as they are thinking about how to discuss their data science research with non-technical audiences, including during job interviews.

By the middle of 2016, the Data Science Institute had graduated its second class of master’s students, with the program rated 6th on a list of “Top 50 Best Value Big Data Graduate Programs,” according to Value Colleges.

Meanwhile, applications to the program soared to 438 by fall 2016.

Other research efforts were also gaining traction, with the institute participating in the development of many successful proposals, including those that received funding from the National Institutes of Health and the National Radio Astronomy Observatory.

Interest in data was also growing at the state level, with the institute holding conversations with Virginia officials, including hosting a state-wide Data Analytics Summit with the governor about how different state agencies were using their data.

The team even created swag that featured a twist on the well-known state tourism slogan for the event: “Virginia is for Data Lovers.” Given the high-profile nature of the visit, gaining approval just for their branding efforts proved to be a significant challenge for the institute in itself.

But their efforts paid off.

It was “great to see them want to be involved in this whole area, the era of big data and bringing data in to inform policymaking,” said Don Brown of those discussions with officials.

Priority was also placed on forging relationships with others in the Charlottesville community who had an interest in data science.

The institute collaborated with local analytics businesses to launch the Charlottesville Data Science Meetup, a group that held workshops and meetings focused on data science issues.

Working with the community has remained a hallmark of the School of Data Science. As Reggie Leonard, whose portfolio includes community engagement, put it: “We’re all connected, and if we can create spaces to bring more people together, then more people will be connected.”

Phil Bourne is a scientist in the truest and most all-encompassing use of the word. He received a Ph.D. in chemistry, shifted his research emphasis to biology, then would later focus on computational science. This was all before he would ultimately become the first dean of the first school for data science in the country.

He made his mark early in his career by developing a protein databank, which is used by approximately 200,000 scientists each month, including in the discovery of new drugs. As a result, he is one of the 10 most-cited scholars at UVA, according to Google Scholar.

“It really had a profound impact on science in general,” Bourne said.

He also worked on developing algorithms that could assist in comparing protein structures, research that helped get more products to market. Underlying much of this work is an emphasis on science that serves society — a principle that now guides his leadership of the School of Data Science.

After a lengthy career in private industry, research, and academia, including at the University of California San Diego, Bourne entered government service, becoming the first associate director for data science at the National Institutes of Health in 2014.

“It was certainly beyond the midlife crisis,” he joked. “This was more toward the late life crisis, and I decided I just wanted to do something different.”

Early in his tenure, he approached NIH Director Francis Collins about what he should focus on. He responded that he wanted Bourne to use data and methods to unify the many siloed NIH institutes and centers.

“This is clearly a huge undertaking to move a big ship like that, but it certainly paid off for the kinds of things that I did when I came here,” Bourne said.

With Don Brown shifting to a more research-focused role with the Data Science Institute in 2017, there was an opening to become the next director.

“I didn’t know much about UVA generally,” Bourne said, though he did recall during a past visit thinking that Charlottesville and the community were “really a hidden gem.”

Ultimately, it was the people at UVA he met and the awarding of degrees that provided sustainability for the Data Science Institute that convinced him that this was a leap worth taking, he said.

Arlyn Burgess vividly recalls her thoughts about the future of the institute early in the process to find Brown’s successor.

“I’m going to need to get a new job because there’s just no way that this thing is going to move forward,’” she recalls thinking.

But then she met Bourne, who requested a separate meeting just with her after his interviews to get a better sense of how things worked.

“His openness and transparency from the beginning was awesome,” Burgess said. “And I knew at that point, if we could get him here, that he was going to be able to work with us to bring it to the next level.”

Burgess remembered Bourne coming to a banquet to celebrate the new class of master’s graduates and telling her that he felt a bit like a stranger in someone else’s house. However, while he may not yet feel a part of it, he said that he could see the family atmosphere that was there, which was energizing and encouraging for what the future would hold.

“It’s one of the things that has always been exciting to me is that it kind of was a family affair,” said Burgess. “We were all in — we were lean, and we were mean, and we were moving fast.”

Bourne would take over as director of the Data Science Institute in May 2017; he was also named the Stephenson Chair of Data Science as well as a professor of biomedical engineering.

“I had no intent to come here and develop a school and be a dean,” he said. “I came here, really, to run a small institute and do my own research.”

His plans would soon change.

While the master’s program continued to attract a considerable number of applicants, it required students to study in residence at UVA.

This was certainly an appealing aspect to many, but for others, this simply wasn’t feasible for any number of reasons. Some were not in a position to move to Charlottesville. Others couldn’t leave their jobs for a year.

Cathy Anderson had collaborated with Don Brown and Arlyn Burgess during the early days of the Data Science Institute to deliver custom executive education programs while she was at UVA’s School of Continuing and Professional Studies.

A couple of years later, in January 2017, Anderson joined the Data Science Institute team as the Director of Executive and Continuing Education, with the mission of expanding the Institute’s offerings to new audiences.

“Don had been interested in venturing into the online space for a while,” Anderson said. “And that’s, of course, most of what the School of Continuing and Professional Studies did, so I looked forward to applying my experience at the Institute.”

Anderson was excited for the opportunity to expand data science education to new markets of students, and soon, attention turned to the idea of creating an entirely online master’s program.

The Data Science Institute, though, was still a lean operation, and establishing an online degree program would require extensive work, including marketing and student recruitment.

Anderson and others realized they would need an outside vendor to turn their vision into a reality and enlisted Noodle Partners, a firm that specializes in assisting universities with these very needs.

Beyond promoting the program, the institute, which did not have its own faculty, had to earn buy-in from other departments, many of whom, Anderson noted, were “very stretched” in terms of resources.

“There was a lot of going around and meeting with people, talking about what we were hoping to do, and listening to their concerns” she said.

With the provost’s office fully supportive, the online data science master’s degree was announced in fall 2018, with the program launching the following summer, one of the first of its kind at UVA.

Given the unique challenges that students in the online program would face, courses had to be designed to accommodate the needs of students and the extraordinary time demands that many faced.

“They need to really know what to expect for planning purposes because many juggle full-time jobs and families,” Anderson said when it came to assignments, tests, and due dates. She also noted that faculty members would record lessons and other content, which allowed students to view them when their schedules permitted.

While this required many instructors to adjust their teaching styles, the payoff was considerable, as data science education at UVA would now be accessible to a much wider pool of talented and passionate students, many of whom would no longer have to take a year off from work or uproot their families to pursue their goals.

“She never gave up,” Brown said of Anderson. “And sure enough, we got the program.”

“Everyone felt really good about this new student population and being able to serve them,” said Anderson. “They’re just so thankful that they have the opportunity.”

That’s true, Bourne added, “but there were moments when we were stretched so thin. I feared we would not be able to deliver classes.”

Indeed, while the expansion of programs and the ambition of the work of the Data Science Institute — and later the School of Data Science —brought success, it did not come without a cost. Resource limitations amid increasing responsibilities would continue to loom large and weigh on the team as the years went on and ambitions expanded.

When the Data Science Institute was launched, there were 11 schools at UVA. The newest was the Frank Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy, which formed in 2007. Before that, a new school hadn’t been created at the University since the 1950s.

Jaffray Woodriff had long wanted to see his alma mater be a national leader and pioneer in data science by creating a school dedicated to it. He previously donated $10 million toward realizing that vision, which helped launch the Data Science Institute in 2013. In the years that followed, he decided it was time for something bigger.

“I got more and more excited about the possibility of making a much larger contribution,” Woodriff said. “I could start to see that my idea of starting a school was being taken seriously.”

Ultimately, the Quantitative Foundation, founded by Jaffray Woodriff and Merrill Woodriff, would pledge $120 million, the largest private donation in UVA history, to create a School of Data Science at UVA, the first in the country.

While the historic donation from Woodriff unlocked the possibility of a school for data science, more work remained to turn it into a reality — in part because little information existed on how to move forward.

“The University doesn’t really have that much in the way of bylaws or guidance about how you form a school,” said Teresa Sullivan.

“We were kind of making it up as we went along,” she added.

With Sullivan’s term set to end on Aug. 1, 2018, they would also need the support of a new University president.

Jim Ryan would take over that month. While new to the role, becoming UVA’s president was a homecoming of sorts.

After graduating first in his class from the University’s School of Law, Ryan clerked for Chief Justice William Rehnquist. He then worked as a public interest lawyer in Newark, New Jersey, before coming back to UVA to join the Law School’s faculty, where he served for 15 years, including as academic associate dean from 2005-09.

He would eventually be tapped as dean of Harvard’s Graduate School of Education, holding that position from 2013-18, then returned to Grounds again — this time as UVA’s ninth president.

Ryan remembered his initial reaction when he first learned about the possibility of a school for data science at the university he was now poised to lead.

“I will confess, I was a little skeptical,” he said.

More specifically, he said: “I wanted to understand the benefit of having a school as opposed to having an institute.” The key figures behind the idea made a convincing case.

“I talked to Terry Sullivan a fair bit,” Ryan recalled. “And she was persuaded, as I ultimately was, that this was an important enough field that having a school dedicated to it made a lot of sense.”

He also spoke with Woodriff and Phil Bourne.

“Jaffray made the point that this will never get the attention it deserves, either internally, among students and faculty, or externally, unless there’s a seat at the table for data science — meaning, that there is an independent school and that there’s a dean of this school,” Ryan said. “And he was right.”

Meantime, Bourne sold Ryan on a vision for the new school, one that wouldn’t be siloed off from the rest of the University.

“Once I started thinking about it that way, it became incredibly exciting to me,” Ryan said.

“It was a different way of creating a school and a different way of interacting,” he explained. “And that’s what ultimately convinced me that this was the right way to go.”

The new president was on board, but considerable work remained to turn this vision into a reality.

Phil Bourne estimates that he and his team spent about a year on outreach and making the case for a new school devoted to data science.

He remembers one meeting that included the deans from throughout the University, as well as Teresa Sullivan, who was still president at the time.

“There was quite a lot of tussling,” Bourne said of the discussions among the 11 other school leaders, with some arguing that there wasn’t a need for a new school and that data science could be carried out in existing ones.

One thing that advocates for a new school had going for them was the track record of success that the Data Science Institute had demonstrated over the previous five years.

“I think people recognized its promise,” Sullivan said of data science and its potential to address new challenges.

From a practical standpoint, she also noted that the University had adopted a new budget model, one that helped ensure existing departments and schools would be properly credited for courses that were offered. She believed the transparency and clarity of this model may have helped mitigate some concerns about the potential resource impact of a new school.

Melody Bianchetto, vice president for finance, led the effort to draft a budget proposal for the impact and opportunities that such a school would provide.

Bourne said their efforts pitching the concept of the school helped sharpen its philosophy.

“It was in those discussions that really the notion of a school without walls came up,” he said. The mission of a new school for data science would not be to compete with other schools, Bourne explained, but to work with them and thereby elevate UVA.

Don Brown said that a key argument for their proposal was the vast potential of the field itself.

“This was an area that was so transformative,” he said of data science, adding that “if we didn’t do it as a school, we wouldn’t really be able to address some of those major transformations.”

By the end of 2018, all 11 deans were supportive. Unfortunately, that information had not trickled down, which Bourne and others realized shortly before a public announcement.

So, the team laid out their plan to the executive council of the Faculty Senate, who, Bourne said, “were completely blindsided.” Then, at the full Faculty Senate, Bourne said their proposal elicited “some pretty visceral reactions,” with professors asking what this might mean for revenue and student recruitment at their schools.

The reaction was compounded by the suggestion that the School might not award tenure. “While I remain in two minds about the value of tenure, it was clearly a huge sticking point,” said Bourne. “I remember Jim Ryan going to the back of the room to get me a glass of water as I tried to defend the case. He came back and said, ‘I think you will need to rethink this.’”

Bourne did rethink it, and in retrospect, it is what the School's own faculty expect. Reinventing higher education can only go so far.

A manifesto would ultimately be drafted by Bourne as a response to Faculty Senate concerns with input from the team laying out exactly what a school for data science would do and why it was needed.

On Jan. 18, 2019, the stage was set to publicly unveil what had been unfolding for months. At a ceremony at UVA’s Rotunda Dome Room, the grant provided by the Woodriffs’ Quantitative Foundation was announced.

At the event, Ryan, who took over as president just a few months earlier, said the school that would be created would be “one driven by the discovery of new knowledge and a commitment to the public good.”

Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam called it “a momentous day for the University of Virginia and for the commonwealth.”

With the gift now public, efforts accelerated to secure final approval for UVA’s 12th school.

In May, the Faculty Senate, despite some initial misgivings, voted unanimously to support its creation. The next month, UVA’s Board of Visitors also voted unanimously to approve the plan.

Finally, at their Sept. 17 meeting, the State Council of Higher Education for Virginia made it official, approving a resolution creating the School of Data Science that would “be responsible for the leadership, management, and advocacy of data science education and research.”

It was the culmination of an improbable series of developments that began just a decade earlier, with Rick Horwitz, Don Brown, and others pitching the idea of interdisciplinary work around big data sets; Jaffray Woodriff’s dream of UVA becoming the pioneering national university for the study of data science; and the hiring of Phil Bourne to make it a reality. A School Without Walls, one that would embody not only the promise of a new field but also the possibilities of interdisciplinary collaboration, had at last arrived.

Arlyn Burgess recounted the January 2019 announcement event and speaking to Woodriff at the lunch that followed.

“I joked with him, and I said, ‘Hey, Jaffray, a school of data science — who would have thought?’” Burgess recalled. “He smiled, and he said, ‘Well, I did.’”